Why The Australian Guidelines on Fluoride Use Are (likely) Contributing To Decay In Australian Children. (An opinion piece and what should you consider doing in your practice)

The NHMRC guidelines on fluoride use were reviewed in 2019 and examined several topics, 2 of which were fluoridated water and toothpastes for children and adults. The summary recommendations supported fluoridated water at the current level in Australia. However, their recommendations of toothpaste use in children should be reviewed. We will explain, over a few steps, why we think this should occur. Keep in mind, this is our opinion after reviewing the risks and benefits of available data, both in Australia and Internationally.

Fluoride Overdose and Poisons Hotline

The major immediate risk of overt ingestion of fluoride is a fluoride overdose. We reviewed the available data and could not find any specific record of a fluoride overdose leading to severe complications. This is not to dismiss the importance of adult supervision in the paediatric population to avoid ingestion of fluoridated toothpastes.

Decay rates in Australian Children

Secondly, let’s look at decay rates in Australian children. The data is a bit dated, however, from 2015 (AIHW: Chrisopoulos S et al) decay rates were:

• Primary Tooth Decay

• 5yr olds = 47.7%

• 10yr olds = 54.2%

• Permanent Teeth

• 6 yr olds = 7%

• 14yr olds = 64.1%

• There are 5 – 10 <4 year olds, out of every 1000, that require general anaesthetic for dental treatment.

So essentially one-in-two young children has decay in their primary teeth and two-thirds of teenagers in their permanent teeth. In remote and vulnerable populations, it is substantially higher. There are also quite a number of children admitted to hospital every year for preventable dental reasons.

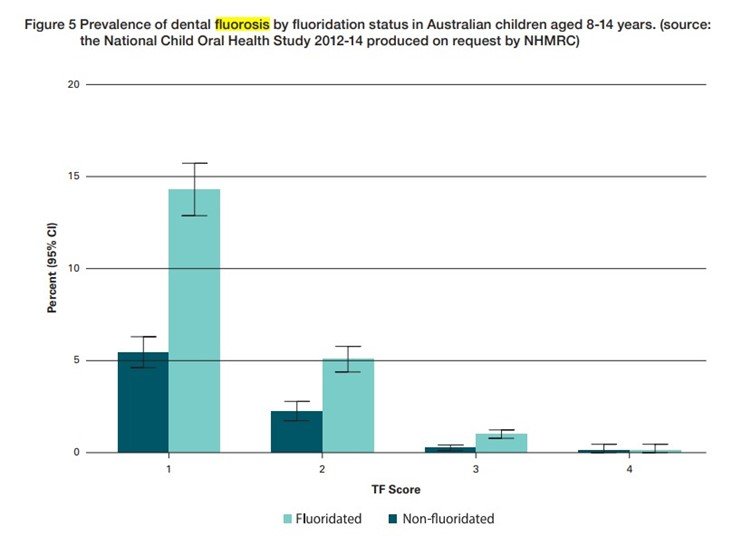

Rates of fluorosis in Australia (and the world)

This leaves us with the primary risk of too much fluoride being fluorosis. Fluorosis in Australian children has decreased over recent decades, most of the data primarily originates from South Australia and is quite dated now (~15 yrs old). We would also postulate that this is prior to, or just around, the standardised definition of hypomineralisation. Many of the photos presented for fluorosis, commonly appear to be misclassified. In that, they only affect the incisors or molars and do not align with a chronological insult such as fluoride.

• However, we can gather rates of:

• 10 – 20 % very mild (not an aesthetic concern)

• 0.8% mild (not an aesthetic concern)

• 0.1% moderate-to-severe (of an aesthetic concern)

What strength toothpaste prevents decay?

This is the crux of the issue. There has been substantial research on this topic, with systematic reviews and Cochrane reviews. We have attached some excerpts from some papers below.

White Paper on Dental Caries Prevention and Management A summary of the current evidence and the key issues in controlling this preventable disease Nigel Pitts & Domenick Zero. https://www.fdiworlddental.org/sites/default/files/2020-11/2016-fdi_cpp-white_paper.pdf

In summary, the most effective preventive agent for dental caries is fluoride. Fluoridated toothpastes need to be 1000ppm or greater to be effective. Anything less than this has insufficient evidence to prevent decay.

International Guidelines

Before we get to the Australian guidelines, lets look at what the rest of the world is doing:

Europe

Toumba et al, 2019, Guidelines on the use of fluoride for caries prevention in children: an updated EAPD policy document.

United Kingdom

National Health Service, 2018. Fluoride - NHS (www.nhs.uk)

United States of America

*US toothpastes are a standard 1000 – 1100ppm

American Academy of Pediatrics.

FDI

So, What About Australia?

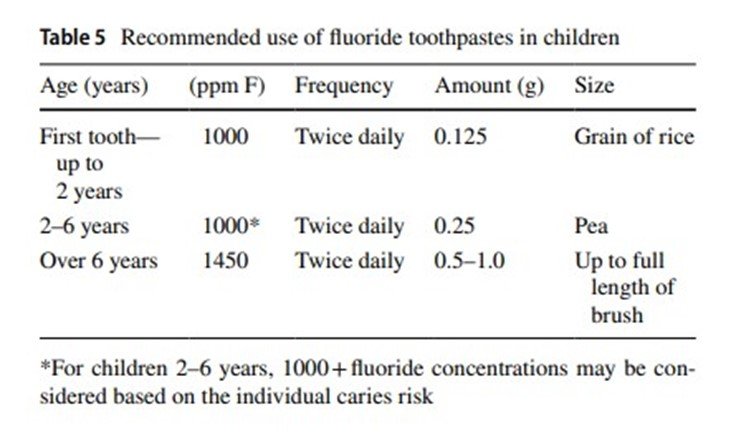

What does the NHMRC, and our professional organisations, recommend regarding fluoridated toothpastes?

• 0 – 18 months

• No toothpaste (This is incredible. What is the evidence behind this??)

• 18 months to 5yrs

• 500-550 (Below a level that prevents decay)

• 6yrs+

• 1000ppm (Children are now exposed to toothpaste that prevents decay, approximately 5 - 5.5 years after their teeth erupt.

• Adults

• 1450ppm

Is This Evidence Based and Helping Our Paediatric Population?

In short, we believe no.

Lets balance the risk benefit equation here,

Half the paediatric population has cavitated lesions. Several thousand of them each year require general anaesthetic for treatment along with innumerable invasive dental treatments in young children.

Then we have no-data on any significant fluoride overdose resulting in severe acute complications and fluorosis rates of an aesthetic concern, of 0.1%...

Anecdotally we see numerous patients every year younger than 2 years with severe dental caries that we perform dental treatment on under general anaesthesia. Their parents have followed the advice of the NHMRC, and their dental practitioner, and used either no toothpaste or one containing 550ppm. There is a dearth of evidence supporting this and therefore we do not reach preventive levels, in Australia, until a child is 6 years of age.

What Do We Recommend?

We recommend that we follow the rest of the world.

0- 3 years (from the time the first tooth erupts) parents clean their child’s teeth with a smear of 1000ppm toothpaste.

3 – 6 years: Parents clean their child’s teeth with a pea size amount of 1000ppm toothpaste. If they are an extreme caries risk move to 1450ppm

6+: Pea sized amount of 1450ppm toothpaste. If they are an extreme caries risk they can be prescribed 5000ppm under strict supervision.

We hope this has been helpful to you. If you subscribe below we are happy to share our oral health information sheets that we provide to parents. Once again, this is just our opinion, but we believe we have solid evidence for why the NHMRC guidelines need to be reviewed.

Sources:

NHMRC, 2017. Information Paper – Water Fluoridation: dental and other human health outcomes. fluoridation-info-paper.pdf

Oral Health and Dental Care in Australia: key facts and figures 2015 AIHW: Chrisopoulos S et al

Toumba et al, 2019, Guidelines on the use of fluoride for caries prevention in children: an updated EAPD policy document

AAPD, 2018, Policy on Fluoride Use. p_fluorideuse.pdf (aapd.org)

White Paper on Dental Caries Prevention and Management A summary of the current evidence and the key issues in controlling this preventable disease Nigel Pitts & Domenick Zero. https://www.fdiworlddental.org/sites/default/files/2020-11/2016-fdi_cpp-white_paper.pdf

Walsh et al 2019. Fluoride toothpastes of different concentrations for preventing dental caries - PubMed (nih.gov)